Art as a Means of Empathy, Inclusion, and Care Through Mutual Support.

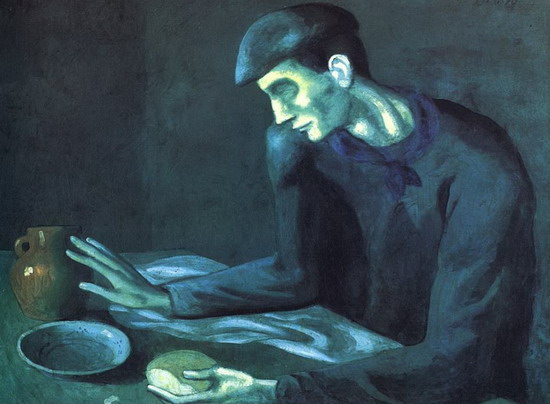

Thus, returning to physical disability, which inevitably serves as fertile ground for discovering a profound truth within us, we must consider and rediscover certain paths that lead to this discovery: such as Art, Empathy, and Mutual Support. These are not merely tools for survival but, when skillfully unleashed, they become "wings." They are the keys to transforming a reality that often seeks to place us on the margins into a dance of meaning, beauty, and connection.

As an artist and as a person with a physical disability, I have learned that every limit is a threshold. At times, I cross it; at times, I do not. But the threshold is not something that defines us; rather, it is an opportunity to redefine ourselves and the world around us. I wish to share with you some reflections that, albeit briefly, encapsulate the power of mutual support, the value of art, and the necessity for a renewed empathetic consciousness.

Especially when that pain is chronic, as the mere awareness that others suffer like we do does not lighten our burden but can even amplify it, making us feel even more alone, prisoners of an injustice that seems to have no escape. However, genuine connection between people—or even between souls is a completely different matter.

What should comfort us is not knowing that others suffer too and thus believing we can talk to them and be more easily understood. Instead, it is knowing that others see us with a deeper level of understanding, listening to and truly comprehending us. This level, which we who are disabled implicitly acquire, is an aptitude that everyone can refine, supported, for instance, by Art regardless of the branch of art one chooses to express themselves in. This is where the possibility lies: between isolation and community, between feeling invisible and feeling accepted and included.

True joy, the kind born of shared pain, emerges when we find those who not only recognize our suffering but embrace it, helping us transform it into something new. Ultimately, I speak of certain branches of Love, which Art, as a universal language, knows how to make bloom.

Art as a Vehicle for Social Inclusion.

If, as already stated, art is a language that transcends words and speaks of us, for us, through us, then as an artist, I can affirm that creating is an act of existence—a way to declare to the world: "I am here. I have a voice. And I deserve to be heard."

Although I personally dislike describing or explaining my work because it does not interest me—I am nonetheless implicitly aware that I am conveying a message. This might be seen as an inconsistency in my attempt to "make art," but what, ultimately, is more inconsistent than art itself? Its nature is intrinsically tied to inconsistency, as it stems from the subjective expression of the human being, which is, by essence, complex and ever-changing.

Moreover, art is not bound by rigid rules or linear logic; it thrives on contradictions, emotions, and intuitions that often conflict with one another. Yet if its ultimate expression is to represent reality in all its fragmented beauty and to stimulate endless interpretations, leaving room for freedom and creativity, how much more open can a suffering spirit be to this form of expression?

For a person with a disability, art can be much more than a means of expression; it can become a tool for social recognition a bridge that overcomes the barriers imposed by disability. It connects worlds that may have become distant due to inevitable prejudices that disability sometimes amplifies.

Empathy: A Consciousness to Rediscover.

We live in a fast, noisy, fragmented world where we are expected to succeed from adolescence onward. In such a reality, empathy seems like a forgotten luxury, an ancient art of understanding for which we have lost the manual. Yet, it has never been more necessary than it is today.

If empathy is not merely an emotional reaction but an act of awareness towards others—the "different"—then it means listening attentively, putting ourselves in someone else's shoes, and, most importantly, acting accordingly. Here, art re-emerges as a language capable of expressing these connections.

How many times have we encountered a beautiful work of art that captivates our soul, leaving us in awe of how its creator brought it to life? This is the glue that binds us together. For those living with a disability, empathy can be the fine line between living with dignity, being recognized in our (partly) new identity, and being left on the margins.

But empathy is not merely a gift we can receive; it is a quality we must also cultivate and offer. When we embrace our own vulnerabilities and those of others, we uncover a profound truth: we are all fragile, all human, all disabled in some way.

If helping others, using art as a tool for inclusion, and rediscovering empathy are the pillars of a life that does not stop at physical limitations, then such a life finds ways to adapt and embrace the complexity of human experience.

Adaptability is not merely an act of apathetic, non-participative survival; rather, it must become an art form that finds its home within Art itself. It is our ability to transform challenges into new pathways even if the opportunity to overcome them is not always given, or we must create it ourselves. In Art, pain becomes expression, and vulnerability becomes connection.

Thus, those who create art are driven by a continuous movement, one in which we shape our inner world to respond to what surrounds us, all while preserving our essence.

Ultimately, what truly matters is not how much we achieve or conquer but how deeply we touch the hearts of others. For it is in that touch, in that authentic connection, that we uncover the most profound meaning of our existence.

Art is the universal language that lives in silence or, at the very least, when it expresses itself, it never shouts, even when it seeks to challenge. The act of creating moves through matter and engages in dialogue with souls. True art never raises its voice nor tramples anyone's path; rather, it becomes a trail for those willing to explore hidden worlds, unspoken ideas, and profound emotions. In art lies a profound truth:

Art is the universal language that lives in silence or, at the very least, when it expresses itself, it never shouts, even when it seeks to challenge. The act of creating moves through matter and engages in dialogue with souls. True art never raises its voice nor tramples anyone's path; rather, it becomes a trail for those willing to explore hidden worlds, unspoken ideas, and profound emotions. In art lies a profound truth: In the creative act whether painting, sculpting, composing music, writing, or any other activity that stimulates us to create art there lies a power that transcends aesthetics and sensory pleasure. Art, in all its forms, is the primordial language through which humanity speaks to itself and the world a silent voice crossing centuries to remind us of who we are and who we might become. But what happens if, instead of viewing art as a final product, we begin to see it as a process, a tool capable of shaping not just our present but also our inner evolution?

In the creative act whether painting, sculpting, composing music, writing, or any other activity that stimulates us to create art there lies a power that transcends aesthetics and sensory pleasure. Art, in all its forms, is the primordial language through which humanity speaks to itself and the world a silent voice crossing centuries to remind us of who we are and who we might become. But what happens if, instead of viewing art as a final product, we begin to see it as a process, a tool capable of shaping not just our present but also our inner evolution?

Art is a universal language that transcends geographic boundaries, linguistic barriers, and cultural differences. It is a powerful tool for expressing emotions, telling stories, and giving form to the ineffable. But why is art so important in our lives?

Art is a universal language that transcends geographic boundaries, linguistic barriers, and cultural differences. It is a powerful tool for expressing emotions, telling stories, and giving form to the ineffable. But why is art so important in our lives? The use of enamel in my work is a deliberate choice, born from the desire to make no compromises with the medium. For me, enamel is a pure language that admits no shades or half-measures. Every brushstroke I apply is a definitive statement, an assertion of presence and intensity. There is no room for hesitation; enamel does not allow for retracing steps, and every gesture becomes final. In this sense, it is ideal for creations that demand an inner tension, which I strive to convey without mediation.

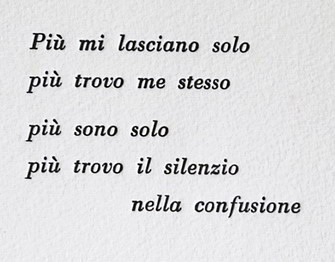

The use of enamel in my work is a deliberate choice, born from the desire to make no compromises with the medium. For me, enamel is a pure language that admits no shades or half-measures. Every brushstroke I apply is a definitive statement, an assertion of presence and intensity. There is no room for hesitation; enamel does not allow for retracing steps, and every gesture becomes final. In this sense, it is ideal for creations that demand an inner tension, which I strive to convey without mediation. Loneliness, for me, is an intrinsic condition of human existence, an inner space that can be frightening but, if embraced, becomes a precious ally. It is not the absence of people that makes me feel lonely but rather the quality of the relationships around me. I often think of Nietzsche and that passage from Zarathustra where he says: "My solitude does not depend on the presence or absence of people; on the contrary, I hate those who steal my solitude without, in return, offering me true companionship." That’s exactly how it feels: superficial connections, which the world is full of, only distract me from my essence. Silence, on the other hand, helps me rediscover it.

Loneliness, for me, is an intrinsic condition of human existence, an inner space that can be frightening but, if embraced, becomes a precious ally. It is not the absence of people that makes me feel lonely but rather the quality of the relationships around me. I often think of Nietzsche and that passage from Zarathustra where he says: "My solitude does not depend on the presence or absence of people; on the contrary, I hate those who steal my solitude without, in return, offering me true companionship." That’s exactly how it feels: superficial connections, which the world is full of, only distract me from my essence. Silence, on the other hand, helps me rediscover it. We live in an age where consumerism dominates our choices, urging us to replace anything broken with something new. This endless cycle not only weakens our connection to objects but also fuels unsustainable waste that threatens our balance with nature.

We live in an age where consumerism dominates our choices, urging us to replace anything broken with something new. This endless cycle not only weakens our connection to objects but also fuels unsustainable waste that threatens our balance with nature.

I believe that being a 'pataphysicist today means, above all, maintaining irony and resisting conformism. It is a way to challenge dogmas and conventions through humour, avoiding the trap of cultural and intellectual standardisation. It is not merely a mental exercise but a true philosophy of life: exploring the absurd and the marginal can become a key to reinterpreting reality.

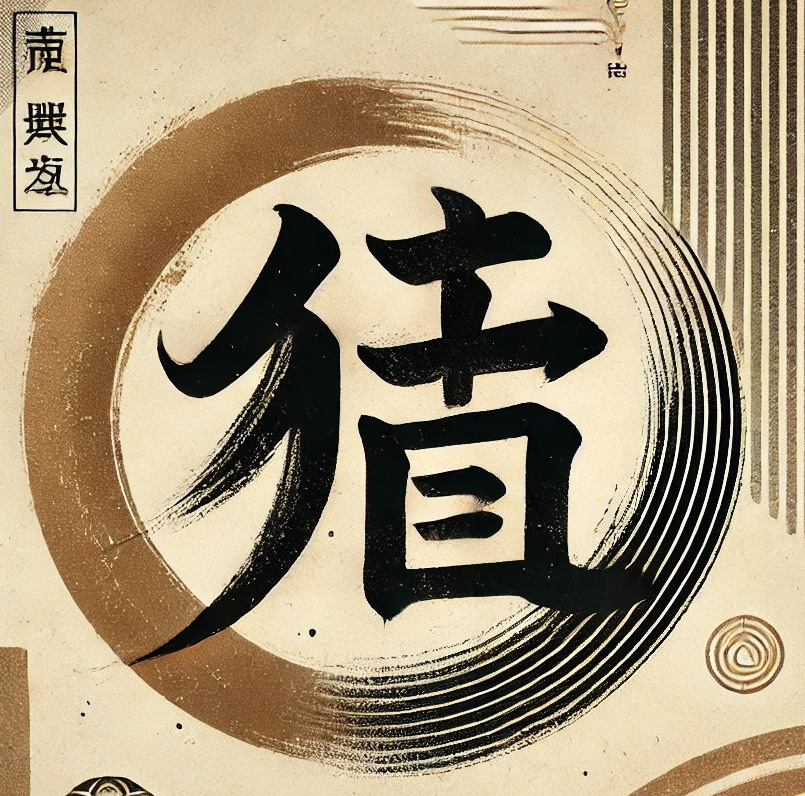

I believe that being a 'pataphysicist today means, above all, maintaining irony and resisting conformism. It is a way to challenge dogmas and conventions through humour, avoiding the trap of cultural and intellectual standardisation. It is not merely a mental exercise but a true philosophy of life: exploring the absurd and the marginal can become a key to reinterpreting reality. Philosophically, *Kurinuki* can be seen as a meditation on transience and imperfection, concepts central to the Japanese philosophy of *wabi-sabi*. Through the practice of *Kurinuki*, the artisan engages directly and immediately with the raw material, embracing and valuing the imperfections that emerge during the process. Each piece becomes a testament to the present moment, to the interaction between the artist and the clay, and to the unrepeatable uniqueness of that encounter.

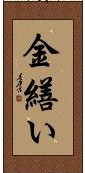

Philosophically, *Kurinuki* can be seen as a meditation on transience and imperfection, concepts central to the Japanese philosophy of *wabi-sabi*. Through the practice of *Kurinuki*, the artisan engages directly and immediately with the raw material, embracing and valuing the imperfections that emerge during the process. Each piece becomes a testament to the present moment, to the interaction between the artist and the clay, and to the unrepeatable uniqueness of that encounter. Kintsugi is an ancient Japanese method of repairing broken ceramics. The word "kintsugi" literally means "to repair with gold" or "to repair with silver." This artistic and philosophical practice involves fixing the fragments of a shattered ceramic object with a mixture of resin and gold or silver powder, thus creating a new form of beauty.

Kintsugi is an ancient Japanese method of repairing broken ceramics. The word "kintsugi" literally means "to repair with gold" or "to repair with silver." This artistic and philosophical practice involves fixing the fragments of a shattered ceramic object with a mixture of resin and gold or silver powder, thus creating a new form of beauty. Raku art represents a unique form of ceramics, originating in Japan, that has spread with great success around the world. This technique is distinguished by its particular firing process, which gives each piece an inimitable and deeply expressive appearance. Raku artists, through their mastery, manage to transform simple pieces of clay into true works of art, rich in textures, colours, and nuances that capture the gaze and the heart of those who observe them.

Raku art represents a unique form of ceramics, originating in Japan, that has spread with great success around the world. This technique is distinguished by its particular firing process, which gives each piece an inimitable and deeply expressive appearance. Raku artists, through their mastery, manage to transform simple pieces of clay into true works of art, rich in textures, colours, and nuances that capture the gaze and the heart of those who observe them.